by Mark W. Roche

A defining aspect of modern art is immersion in the ugly: works that portray physical or moral ugliness, whose form is distorted, or whose parts seem to be at odds with one another. Many would thereby lament how far we have come from the tradition of great Christian art. But such a contrast would be mistaken.

Immersion in the ugly is hardly unique to modernity. The ugly surfaces in a prominent and sustained way for the first time in the Roman era, specifically in the imperial age. Ovid and Seneca, even more so Lucan and Juvenal present us with the ugliness of reality. We see not only an inadvertent focus on the ugly as part of a turn to realism, but also a conscious disgust with the world. Senselessness and absurdity define the tone of Lucan’s engagement with the civil war between Caesar and Pompey. In Roman satire, moral ugliness emerges for the first time as the focus of a literary genre.

Christianity represents a second revolution in aesthetic engagement with the ugly. We see this in at least two different ways.

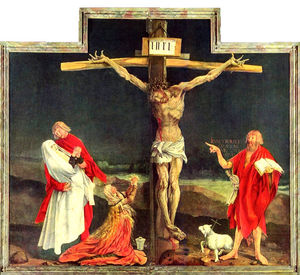

Although Christ was depicted early on as crowned ruler and judge, victor over the cross, his image changes with the humanism of the 11th century and beyond. Christ, no longer the distant creator and judge, suffers torment. The head of the crucified Christ is shown to the side, the arms are pulled away from the now twisted body, the legs are crossed, with one nail replacing the previous tradition of two (and even earlier no nails), the face expresses agony, blood flows from the wounds, and the crown of thorns is introduced. We also begin to see the stigmata. Such works offered more connection than veneration for a population suffering from wars and plague.

In 1515 Matthias Grünewald painted the Crucifixion scene of his Isenheim Altarpiece for the hospital church at Isenheim in Alsace. The work, which gives Christ some of the symptoms of plague-like illness, allowed for those who were suffering to identify with the work. The horrors of this suffering, the distortion of Christ’s body, the widespread wounds render vivid the claim that Christ’s passion involved the ugly and undignified.

Christ laid aside his pure divinity and majesty and humbled himself, suffering and dying as a human. He was “made like his brethren in every respect” so that he could identify with us in our suffering and “sympathize with our weaknesses” (Heb. 2:17-18; 4:15). On the cross Christ was despised and humiliated, treated with contempt. The ugly, the deformed, the low were linked with Christ and with Christianity, but they were ennobled. The abject could carry the seeds of the divine.

Beyond the focus on Christ’s suffering we recognize an increased attentiveness to evil, including human vice, the devil and his various temptations, the seven deadly sins, macabre images of death, which remind us of our vanity and ephemerality, and the last judgment that awaits us, including of course depictions of hell.

It is telling that the greatest Christian writer of all time should be known above all for his depictions of hell. The Inferno has always been the most read of the three parts of Dante’s Divine Comedy. Dante offers us tortures and torments of all kinds–from the most expected to the most imaginative. The devil himself, along with his seductive temptations and brutal torments, represents a new subject for art.

A gruesome image of decay is The Dead Lovers (ca. 1470), with two emaciated humans, their skin wilting and rotting, infested by flies, snakes, and toads. In Hieronymus Bosch’s triptych The Garden of Earthly Delights (1490-1510), the right panel depicts the ugliness of damnation and hell: explosions and a river of blood along with images of torture and cruelty, monstrous creatures of various kinds, bizarre distortions, vomiting, and excrement.

The Christian world was able to tolerate such ugliness well before the ugly became a more widely accepted aesthetic category. Why?

I would like to suggest three reasons.

First, for Christianity the lowliest, most wretched person, however ugly in word or deed, has an innate dignity. The lowliest of humans are the servants of God with whom Christ most identifies: “God chose what is foolish in the world to shame the wise, God chose what is weak in the world to shame the strong, God chose what is low and despised in the world” (1 Cor. 1:27-30). God is not simply otherworldly, but one with us in our suffering and sins. Christ expresses thereby solidarity with the despised and forsaken, the poor and miserable. Even today, one tends to see more wretched images of the crucified Christ in developing countries and more refined images in wealthier countries.

In his magisterial book Mimesis, Eric Auerbach has shown how the Christian worldview altered our aesthetic sensibilities. Much as the noble Christ could be portrayed as ugly, in the humility of his crucifixion, so could the lowly servant Peter be lifted out of comedy and into tragedy, with his betrayal of Christ. A fisherman who has no political role, a servant who thinks he knows more than his master and doesn’t–such a person belongs in comedy. The style with which Peter’s lies are narrated is a lower style, not elevated, the style of comedy. And yet the Gospel account of Mark ennobles St. Peter, a simple person, to tragic stature. When Peter denies Christ three times and weeps, we weep with him.

The idea of the all-loving god, an idea embedded in the incarnation, makes possible the idea that all persons have dignity, all persons deserve our sympathy, and so it breaks apart genre expectations. The finite and lowly is capable of revealing and embodying a higher truth; the lowly human is evocative of transcendence. Caravaggio beautifully captures this concept of Christian humility, the intertwining of the undignified and the transcendent, with the dirty feet and soiled cap of the worshipers in Madonna of Loreto (1603-04). Also the Madonna of the Rosary (1606) elevates poverty and simplicity over the normal rituals of piety.

Second, Christianity’s fascination with the ugly stems from a new recognition of the human capacity for evil. Plato argued that if one knows the good, one necessarily does the good. Knowledge is virtue. Christianity offers a different worldview. The Christian emphasis on the will as a link or barrier between knowledge and action led to a much greater perception of the human capacity for evil. Moreover, in the Christian worldview, knowledge need not lead to goodness. The devil can be knowledgeable, indeed may have abundant insight and formal intelligence. In Shakespeare’s dramas, evil persons, such as Iago, often enjoy their intellectual superiority. In Goethe’s Faust Mephisto has the most captivating and rhetorically fascinating role.

The Christian world recognizes sin as a central element of the human condition, one related to both the fall and the need for a savior. In other words Christ would not be necessary if we were not so bad, the world not so corrupt. This is a general Christian insight, one that has been emphasized more or less at various times, just as different Christian thinkers have come forward with different views on the possible salvation of all. The two are related, for when the deep capacity for sin is coupled with the fear of eternal damnation, ugliness confronts one both in this world and beyond. Whereas the ancient world had systematized the virtues, recognizing the four cardinal virtues and their interrelation, it had not done the same for vice. The Christian world, however, evolved the concept of the seven deadly sins. A writer such as Dante and an artist such as Bosch would be unimaginable in the Greek world.

Third, the ugly and repugnant were implicitly recognized as transitory and part of a larger tale of promise and redemption. The Christian fascination with ugliness is part of a larger redemption narrative. It is easier to focus on negativity, if you have the expectation of eventual harmony. Within that horizon, the human mind finds it more palatable to descend into the depths. Christianity sees suffering as part of a divine plan and so takes us beyond the dying God. Grünewald painted the crucifixion with salvation in mind; his Resurrection belongs to the same altarpiece.

Still, not all Christian art immerses itself in the ugly. But a Christian art, as in Grünewald and Caravaggio, that is realistic and not otherworldly or triumphalist, is able to do justice to the gruesome aspects of reality without losing itself in them, as becomes common in modernity. And here one is right to contrast much of Christian and modern art.

Mark Roche

Rev. Edmund Joyce, C.S.C., Chair

Professor in German Language and Literature

2012-2013 NDIAS Fellow